Expert Q&A: tried-and-true strategies

Expert Q&A: tried-and-true strategies

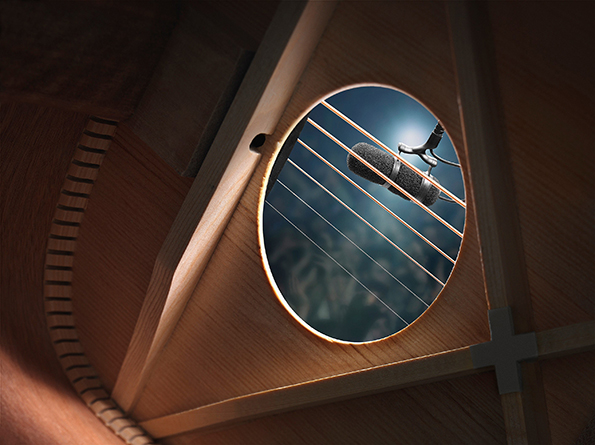

If you ask Vincent Gabriel Antonini, CTS, National Sales Support / Business Development Manager for DPA Microphones in USA, instrument microphones should receive the same level of consideration and care as the pastor’s microphone.

“Some people respond better to music, and some to the spoken word,” he says. “Both options tell the story; they’re both interpreting the Word.

“In today’s worship centers, my opinion is that both are equally important — if only for the reason that they serve the church’s purpose intent, which is to widen participation,” he continues. “A simple, elegant and natural solution is what’s needed to capture the pure sound elements of live music. It’s there that we turn the sound waves into electronic signals through a wire > through sound reinforcement > back again to sound waves to the listener’s ear. Premium-quality microphones will get this chain of events started out on the right path.

“Visual appeal through an uncluttered stage area — minimizing tripping hazards, as well as easier setup and teardown times — can now be realized.”

With such an important message to convey musically, it makes sense to brush up on some proven, professional instrument miking strategies.

Q: Very often, the same church will offer a solemn, traditional service, as well as a more contemporary service — with music to match. Do instrument miking techniques also differ, then?

In practical terms, not so much. We want to capture the source with the least amount of microphones, and we want to position the musical elements physically so that they do not sonically impede each other.

First and foremost, the way I’d go about treating the two different types of service initially is to listen to the room. What’s the acoustic footprint? Is it too reverberant? Is it too non-reverberant? Choosing the correct microphone polar pattern, proximity calibration distance and mounting solution is how you win most of the sound battle before it begins. The sound that will inevitably leak into other microphones will then be at a lower level and thus give the operator more control and power to balance the mix without over-processing or attempting to use EQ to remove unwanted sound (if the mic is linear both on / off axis). It will also help if the engineer attends a few rehearsals to find out if he is dealing with professional or amateur performers. Inconsistencies and un-dynamic players can cause havoc and disrupt the flow of worship very easily. Even in this scenario, having a true sonic image will give you an upper hand. Designing the physical placement of the musicians will also assist the sound quality by allowing the engineer to use fewer mics and acquire premium-quality sound with less risk of comb-filtering. This is caused when two or more microphones receive a source sound at different time intervals, causing unnatural sound artifacts (unaligned). This cannot be rectified easily in a live scenario. When it comes to choral music, we want to avoid having adjoining choral sections from entering other sections’ microphones on-axis at the same level. The 3.1 rule deals with minimizing the audible phasing problems when summing a number of microphones to mono. The rule states that the source-to-microphone distance of numerous microphones should be three times the distance between the sound source and the nearest microphone.

A rule of thumb for minimizing phasing issues is to have around a 10-dB difference in level between the microphone contributions. The 3:1 distance rule achieves this.

A rule of thumb for minimizing phasing issues is to have around a 10-dB difference in level between the microphone contributions. The 3:1 distance rule achieves this.

Another workaround is to pan microphones in the mix. Due to the nature of panning, this also creates level differences.

The DPA supercardiod d:screet™ sc4098 is well-suited for miking choirs. It is a lightweight ceiling- or stand-mounted gooseneck microphone that will naturally lower the sound level of adjoining sections, as well as create a uniform sound level when aimed towards the back row of the choir or the farthest vocalist from the on-axis point. It sort of mixes the levels for you when installed properly; this is great for both volunteers and seasoned engineers.

The best-sounding choir will always have a desired amount of the room ambiance in the mix. Live, the choral voices will combine with the space as it gets pushed through the sound reinforcement system. It will sound fantastic on the recording, as well. Less is more in this case!

I’ve also worked with barbershop quartet-like vocal setups in churches, where vocalists sing together — without instrumentation.

In this case, too, less is more … as long as you’re using well-designed microphones. Or sometimes just one, like the DPA d:dicate™ 4015 wide cardioid capsule. This will capture all the voices while rejecting the congregation side of the equation.

Finally, some pastors like to cantor (sing liturgical music). For them, I’d recommend the microphones we discussed, at length, in our previous article. DPA microphones are a great option for this because of their linearity, transient response and SPL handling. Whether it’s a headset microphone, a necklace microphone or a podium microphone, you’re able to sing and not have technical issues arise from the microphones ability to perform spoken word or music. The microphone will also be closer to the source — the mouth.

Q: Which instruments do churches seem to have the most tro uble miking?

uble miking?

It’s worth noting up front that a lot depends on the consistency and professionalism of the musicians. In the wrong hands, a musical instrument can be a dangerous weapon! When people can sing or play their instruments with good dynamic control or well enough to play within the song arrangement, it immensely helps the front-of-house mixer and monitor engineer. (They can, for example, count on the drummer not to go ballistic when the singer is at the quietest passage of the song.) With that said, most acoustic instruments like guitar / drums / human voice tend to be the most troublesome, especially when the player is inconsistent regarding dynamics.

However, when a worship band is made up of experienced musicians, I’ve found that drums and electric guitar are the instruments most likely to sound loudest to worshipers. Acoustic guitar tends to be the hardest to have sit in the FOH mix and the hardest mic to send back into the musicians’ monitors without feedback issues. A lot of mixers use the direct output (DI) box for this purpose, but it does not sound as good as a microphone can. Using a mic with supercardiod pattern, mounted directly on the instrument, and has a linear on / off axis frequency response like the 4099G will give you more gain before feedback and allow more level into the monitors.

Approach the worship band setup as if it’s performing in a recording studio, even though it’s live. Muffle and pad the drums; put a pillow in the kick drum; put some Moongel (damper-gel) on the tom-toms, or even the cymbals. You can even use more old-school approaches, such as moleskin padding — whatever it takes to tame the drums. That way, you’ll still hear them nicely, but they’re more controllable. Some facilities will use a plexi-glass cage for the drums; but in my opinion, this can create a boxed-in sound and increase off-axis drum energy in all the drum mics, causing lack of separation. Visually, it adds glare and can appear odd.

You might also consider electronic drums, especially if your church relies on a variety of volunteer mixers and drummers. This way, they can play the drum set as hard or soft as they want; either way, the output is controlled by a volume knob, and can be volume-adjustable. This is a great solution for amateur drummers, and can also be a great solution when the band is all using in-ear monitors. This allows control of the drums at the desired level and will not destroy the dynamics or song arrangement.

The only problem is, other band members might want to feel the drummer behind them; that has a certain spiritual and emotional appeal. So, I usually send the electronic drums to a separate wedge monitor facing the congregation and seated next to the drummer. This way, if you’re the singer, bass player or guitarist, it will sound like there’s a real drummer behind you, with a real acoustic set.

Angle the electric guitar amp away from the congregation and place a microphone on the amp and feed the appropriate monitors with its signal. Here again, control through separation wins the day.

Q: When we talk about “instruments,” are we also talking about vocalists?

Yes, definitely. In fact, as important as it is for the pastor’s voice to be heard, it’s just as important that the worship band leader and background singers are heard. It’s a very emotional part of the worship service.

So often, I hear, ‘We have $1,000 dollars, and we need five microphones, so let’s go see what we can get.’ It really warrants more consideration.

For background singers: You need to design these situations. Background microphones will require rejection from the side. Why? You don’t want too much of vocalist 2 going in to vocalist 1’s microphone, and vice versa. By designing your performance with the correct directional characteristics, you can tame unwanted sound from other vocalists and other instruments. This improves the operator’s chances of delivering a well-balanced, uncluttered, fantastic musical experience.

For the lead singer: Here, it can be similar — if the singer is by himself or herself, you can have the monitors set left and right with a supercardioid microphone, and then reject everything from, say, 135 to 150 degrees off-axis. This will allow for more mobility within the singer’s area. If he or she plays an instrument, this polar pattern — with proper mic positioning — will also reject the instrument considerably.

With fewer frequencies flying around the room, invading other performers’ microphones and coming back into the wrong monitors, control is now possible.

Here’s another classic scenario: Bobby wants to hear more of Susan, and Susan wants to hear more of Susan, and Janet wants to hear more of Steve. In these cases, I usually suggest shutting everything off when doing a sound check. Turn off the monitors. The musicians should just have their amps on, nothing else — turn off the PA. Just play.

Then, ask each musician what he or she cannot hear. Most likely, they will hear the louder instruments (like drums and electric guitar) just fine; they might also be OK with their own levels. So, now we can use a deductive approach and only send into the monitors what each person cannot hear well enough.

This will give the performers a comfortable environment. It will also give the engineer less unneeded sound in the room. Everybody wins, including the congregation.

If you leave it up to the musicians, they will say, ‘Give it all to me.’ But, remember what I always say: There’s no right way to do the wrong thing.

— Reporting by RaeAnn Slaybaugh