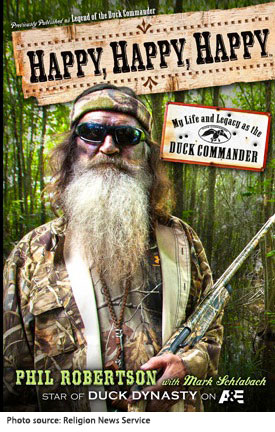

On December 22, 2013, images and footage of America’s infamous, bearded duck hunter flooded primetime news headlines. What’s the buzz about? In an interview with GQ magazine, Phil Robertson — a Southern, fundamentalist Christian hunter from the popular A&E series “Duck Dynasty” — called homosexuality a sin. The network decided to suspend the reality star because of his controversial remarks.

On December 22, 2013, images and footage of America’s infamous, bearded duck hunter flooded primetime news headlines. What’s the buzz about? In an interview with GQ magazine, Phil Robertson — a Southern, fundamentalist Christian hunter from the popular A&E series “Duck Dynasty” — called homosexuality a sin. The network decided to suspend the reality star because of his controversial remarks.

The backlash against the Louisiana family’s expression of its religious beliefs sparked a nationwide debate of religious intolerance.

To some, Robertson’s words simply reiterate the duck hunter’s personal idea of “core Christian values,” the belief that the sanction of marriage should be reserved for man and woman.

To others, his statements tend toward “hate speech” because they outwardly condemn homosexuality and homosexual marriage, as well as tending to resist the trend toward “diversity, acceptance and tolerance.

In what Fox News reporter Howard Kurtz calls “a classic case of corporate spinelessness,” A&E has since reversed its decision to remove Robertson from the show. So, who wins? Does Robertson have a Constitutional right to keep his reality TV contract even while exercising his (however controversial) beliefs?

Although Robertson’s words are often politically incorrect, crude and arguably rather harsh, the controversy brings forth a separate topic of interest to the church law practice: the right to exercise religious freedom. The situation exposes a series of legal questions. In addition, the network’s decision highlights the tension in our free society between rights of business owners in contrast with rights within the governmental sphere.

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution reads: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances

Does the network suspension of Phil Robertson interfere with his Constitutional right to free expression?

The first, if somewhat obvious, observation is that we’re not talking about an action taken by Congress. In Robertson’s case, we’re talking about the actions of two private parties and their contract rights.

In simple terms, the free enterprise system allow private parties to contract (i.e., hire television performers) with whomever they choose. Thus, Robertson doesn’t have a “Constitutional right” to force a television producer to hire him. If the company doesn’t like the color or size of his beard, the sound of his duck call, or just the cut of his suit, then they don’t have to hire him in the first place, or continue to employ him. It follows, then, that the company could “vote with their feet” in deciding that he’s not a good spokesman for their company. In this oversimplified sense, the company wasn’t violating his rights by suspending him or even by terminating the relationship.

Just as Robertson is free to express his views, the company is free to choose another spokesman.

A&E is not a government agent acting under governmental authority. Whenever we attempt to analyze a Constitutional issue, it’s important to distinguish between the actions of the government versus the actions of private citizens.

So, when we analyze Robertson’s comments, it’s important to note that he’s not running for Senate in Missouri as a Republican. If he were speaking on behalf of a governmental entity (or even on behalf of, say, the Republican party), the GOP would have disowned him immediately. But, Robertson isn’t a politician. He’s not a mouthpiece for a political party that’s trying to create or to maintain a national image.

Rather, his remarks reflect the views of a cultural subset. Protecting his privacy isn’t an issue since he clearly qualifies as a “public figure” due to his presence on a television show. But, his popularity with this segment of our culture makes his case important for the conservative wing of the Republican Party.

Conservative Republicans defended him not so much because his Constitutional rights had been violated, but because he gives voice to a point of view which is important to a significant Republican constituency.

“If you believe in free speech or religious liberty, you should be deeply dismayed over the treatment of Phil Robertson,” says Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas. “Phil expressed his personal views and his own religious faith; for that, he was suspended from his job. In a free society, anyone is free to disagree with him — but the mainstream media should not behave as the thought police censoring the views with which they disagree.”

However, note that the “thought police” at work weren’t government agents. Senator Cruz overstates the analogy since the television company was acting to protect its advertising revenue, not acting as a government agent to curb free speech. In the free enterprise system, the exercise of one’s right to speak “freely” (i.e., “free” speech) clearly isn’t always truly “free” of economic consequences.

“The politically correct crowd is tolerant of all viewpoints, except those they disagree with,” says Gov. Bobby Jindal, R-La. “I don’t agree with quite a bit of stuff I read in magazine interviews or see on TV. In fact, come to think of it, I find a good bit of it offensive. But, I also acknowledge that this is a free country, and everyone is entitled to express their views.”

Did Robertson do anything wrong, legally? Robertson’s statements aren’t a crime and didn’t violate any specific person’s Constitutional rights. They did create a potentially serious economic challenge for his employer, A & E.

Should one be able to accurately quote the Bible? Our Constitution protects our right to freely practice our religion without undue interference by our government. This free exercise certainly includes quoting the Bible in an interview.

It doesn’t, however, protect us from the economic consequences of this action if our contract partners are offended by our remarks. (For more examples of how the distinction between private actions versus government actions in analyzing Constitutional questions, see my Nov. 20, 2013 Church Executive blog, “May I legally share my faith in the workplace?”

Robert Erven Brown is an attorney licensed to practice in Arizona. He and his nonprofit practice group work with nonprofits and churches helping them manage key operations connected with their missions, visions and causes. As permitted by local Rules of Ethics, they collaborate with attorneys who are licensed in states other than Arizona. Bob is author of Legal Realities: Silent Threats to Ministries, which describes his Campus Preservation Planning© initiative — a comprehensive program designed to manage the wide array of risks facing non-profit organizations. He can be reached by email or by calling 602.744.5748. RHL is located at 201 North Central Ave., Suite 3300, Phoenix, AZ 85004.

Robert Erven Brown is an attorney licensed to practice in Arizona. He and his nonprofit practice group work with nonprofits and churches helping them manage key operations connected with their missions, visions and causes. As permitted by local Rules of Ethics, they collaborate with attorneys who are licensed in states other than Arizona. Bob is author of Legal Realities: Silent Threats to Ministries, which describes his Campus Preservation Planning© initiative — a comprehensive program designed to manage the wide array of risks facing non-profit organizations. He can be reached by email or by calling 602.744.5748. RHL is located at 201 North Central Ave., Suite 3300, Phoenix, AZ 85004.

This publication is offered as a public service by the Nonprofit Practice Group at Ridenour, Hienton & Lewis (RHL) for general educational purposes to provide accurate and authoritative information on general principles of law. It is not intended to provide, and may not be relied on as, legal advice. The publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, then services of a competent professional person should be sought. “From a Declaration of Principles jointly adopted by a Committee of the American Bar Association and a Committee of Publishers and Associations.” This article may not be used as a substitute for competent legal advice from a licensed professional attorney in your local jurisdiction. No “informal” legal advice will be provided by telephone. Simply sending an e-mail to Mr. Brown will not create an attorney-client relationship. A formal attorney client relationship will not be established until a conflict check is completed and an engagement letter has been signed by both the attorney and the client.